THE PEOPLE OF EAST GWILLIMBURY

Bulletin Magazine - Vol. 17 No. 2 - March 2015

The making of a champion - the Whipper Story

By Blair Matthews

The world of professional wrestling has always been filled with dropkicks, sunset flips, “good guys” vs. “bad guys”, and lots of yelling.

The world of professional wrestling has always been filled with dropkicks, sunset flips, “good guys” vs. “bad guys”, and lots of yelling.

The Golden Age of professional wrestling may not be known for its flashy rock concert atmosphere that today’s wrestling has morphed into, but make no mistake about it – there has always been a certain degree of soap-opera-ish aura surrounding it.

Yes, even in the 1950s when pro wrestling enjoyed a unique relationship with its fans via weekly television shows, the outcome of the matches were pre-determined.

At the time, it was a closely-guarded secret code amongst the wrestlers – anyone from the outside world must never be told that wrestling is scripted.

‘Whipper’ Billy Watson, perhaps one of Canada’s most famous professional wrestlers (and at one time, a resident of Sharon), lived by that code from start to finish.

Born William John Potts, ‘The Whip’ spent the early part of his wrestling career trying to make a name for himself in England. He spent 4 years abroad honing his craft in front of crowds in the late 1930s. He ended up being sidelined for 6 months with a fractured shoulder and broken ribs.

Undeterred, Whipper yearned to wrestle in the spotlight at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens – a territory run by promoter Frank Tunney. Whipper sent a promotional package to Tunney, hoping to get a slot in Toronto; Tunney, as it turned out, hadn’t even bothered to pick the parcel up at the local post office before Whipper was back and ready to prove that he could hold his own in Tunney’s ring.

It didn’t take long.

Seven months later, Whipper was the star that Tunney yearned for.

He had the right look: big, ruggedly handsome, and in Tunney’s eyes, a textbook clean-cut ‘babyface’ fan favourite that people would pay to see.

Whipper regularly headlined shows in the Tunney territory – not just in Toronto, but in smaller towns like Newmarket, Sutton, and Kitchener. He tusseled with the likes of Fritz Von Erich, Gene Kiniski, Yukon Eric, Killer Kowalski, The Sheik, Lou Thesz, and perhaps his most notable opponent, ‘Gorgeous’ George.

Greg Oliver, a Toronto-area sports writer and columnist for SLAM! Wrestling has studied the era of The Whip astutely.

“Canadians needed a hero,” Oliver says. “Just like ‘Gorgeous’ George was the right man at the right time in the U.S., for us it was Whipper Watson. If that doesn’t speak to the difference between the U.S. and Canada, I don’t know what does. Blond peroxide star ‘bad guy’ (George) becomes legendary in the U.S. and here we have a clean-cut hero that preached nothing but good deeds.”

On March 12, 1959, 14,000 fans flocked to Maple Leaf Gardens to see ‘Gorgeous’ George vs. Whipper Billy Watson. Just five days earlier, Tunney had announced the stipulations of the match. If Whipper won, ‘Gorgeous’ George would have his long blond locks shaved off in the middle of the ring. But if ‘Gorgeous’ George could beat Whipper, he’d be forced to retire from wrestling forever.

Just as it looked certain that Whipper would win with his sleeper hold applied to George, Gene Kiniski stormed the ring and attacked Whipper. The match was ruled a disqualification against George due to outside interference; Whipper had won, but was getting a beatdown from Kiniski. The locker room emptied as the ‘good guys’ ran out to come to Whipper’s aid. Kiniski was chased off, while George Hansen, from the Maple Leaf Gardens barber shop, donned a white coat and gave ‘Gorgeous’ George a buzz cut.

The fans loved every minute of it.

If there was ever any doubt about how big a hero Whipper had become in his wrestling heyday, consider this excerpt from a 1944 Maclean’s Magazine article: “(Watson is)...the living embodiment of all the ideals of the Boy Scout movement and the Legion of Decency. Watson is as handsome as Robert Taylor, as powerful as the SS Queen Mary and as persistent and uncompromising as Dick Tracy in his efforts to exterminate evil. In moments of supreme exasperation he is likely to mutter ‘Oh, fudge!’ but otherwise conduct is exemplary. He is a paragon of virtue in the ring. If his opponent attempts to decapitate him with a tomahawk, misses and imbeds the tomahawk in one of the ring posts, Watson will help him to disengage the weapon. If his opponent strikes him illegally with a brass knuckle, Watson merely will smile a sad, brave smile and break his opponent in twain, like a stick of dry macaroni. Watson destroys his opponents with the air of Sir Galahad repelling scorpions, and the customers love him to pieces.”

Oliver says that wrestling in those days was part of the culture. “We are spoiled in a world of 500 channels now, where there’s all sorts of different entertainment. Back then, wrestling was one of the only things you could see on TV and then go see live,” he says. “Hockey had the idea of only showing the first period to make sure people would go to the games. With wrestling you could see the matches and then go and see them live. Whipper capitalized on that, and was certainly smart enough to really run with it. His pop that he sold, his safety club, his attempts to run for public office were all related to his knowledge that his name meant something.”

So much, in fact, that for a brief moment in time, Whipper was more famous than Elvis Presley. The two met briefly once, with the young Presley starstruck – he himself was an avid wrestling fan.

Over the course of Whipper’s 35-year wrestling career he won the NWA/NBA World Heavyweight Championship twice and NWA British Empire Heavyweight Championship a dozen times.

On November 28, 1971, Whipper teamed with Bulldog Brower at the Gardens to beat Diego the Sundowner and Man Mountain Cannon. It was the last time he’d step through the ring ropes as a professional wrestler – 2,422 documented matches later.

It was a fateful winter night two days later when Whipper’s wrestling career came to an abrupt end. But it wasn’t an incident inside the ring that forced him to retire - it was an unfortunate car accident that changed his life path forever.

A car skidded out of control slamming into him as he loaded a fireplace screen into the trunk of his Cadillac, crushing his legs.

It took 3 1/2 hours of emergency surgery at Northwestern Hospital to repair the damage to his left leg. He ended up in a wheelchair for almost a year.

As a prominent public figure – one of the first Canadian professional wrestlers to cross over into mainstream celebrity status – Whipper had always done some degree of charity work. But when he knew he’d never wrestle again, he decided to use his household name and exemplary reputation to help those with disabilities.

For years he had been meeting kids with physical disabilities, telling them that he understood their challenges. His own accident and subsequent recovery told him otherwise and his fall from grace showed him where he needed to go with his life.

“For 25 years I had been putting my arm around kids and telling them things would be all right. I was wrong. For 25 years I had been lying to those kids,” Whipper told a Toronto Sun reporter in 1990. “Now I’m straight with them. No sugar-coating. Because life for the disabled is always going to be tough...”

Sometimes the old adage is true: when one door closes another one opens. It was during his stint in physiotherapy that he met his second wife, Eileen (his physiotherapist).

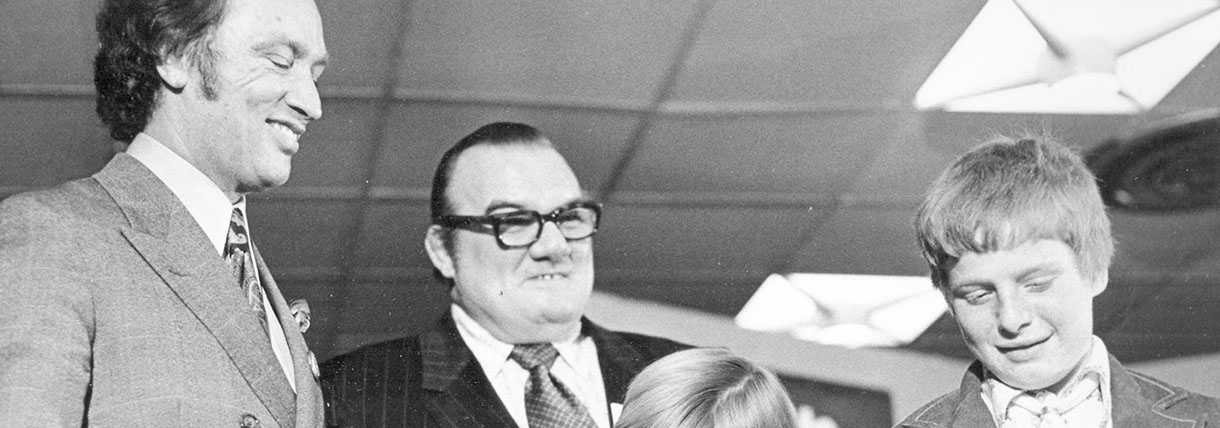

And he crossed paths with East Gwillimbury resident (and now a newly-elected member of East Gwillimbury Council) Joe Persechini.

Whipper and Persechini met in 1977 at an Easter Seals fundraising event. By then, Whipper was a director of Easter Seals and Persechini headed up the Persechini’s Easter Seal Run/Walkathon in Newmarket.

Easter Seals provides programs and services to children and youth with physical disabilities to help them achieve greater independence, accessibility and integration. They also help purchase essential mobility equipment such as wheelchairs, walkers, ramps or lifts.

Every year, an Easter Seals representative and beneficiary is selected as an ambassador for the event. In the 1970s, these ambassadors were known as “Timmy” or “Tammy”. They have since dropped the names, but the ambassador concept remains.

Whipper was brought in as a guest speaker for the Newmarket Easter Seals event, much to the delight of participants, and especially Persechini.

“In the 60s I used to watch him wrestle on CHCH TV at 4 o’clock,” Persechini recalls.

After they met in Newmarket that day, the two eventually became friends, and partnered together to raise funds for many local causes: Georgina Cultural Centre (which houses the Stephen Leacock Theatre); Whipper Watson therapeutic pool (at Southlake Hospital); a year-long campaign to buy a CATscan machine; and many Easter Seals events and telethons.

He supported a huge list of Canadian groups outside of his work with Easter Seals including: the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; the Hugh MacMillan Centre; the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada; the Bob Rumball Centre for the Deaf; and the Canadian Paraplegic Association.

One of Whipper’s best-known charity events was the ‘Whipper Watson Provincial Snow-A-Rama for Timmy’ that he founded in 1975. The event was a snowmobile trail ride where participants would solicit pledges to raise money for Easter Seals. In its first year, 12 communities participated and together raised $130,000. Since the inaugural year, Snow-A-Rama has raised more than $16 million in at least 20 communities. The event still continues every year in places like Timmins, Walkerton, Morrisburg, and Kemptville.

Over time, Persechini says Whipper became like a father to him, and taught him how to better himself while treating others with respect. And anytime Whipper took on a new fundraising cause, Persechini was right there beside him.

“We had some really good times along the way,” Persechini says. “We had many dinners at my house, many dinners at his house.” They went jogging twice a week together, and along with a few other friends, often went fishing.

On more than one occasion, Persechini remembers Whipper telling him that every time he did a speaking engagement it was like being in a wrestling match – he gave all his energy to the crowd, he spoke from his heart, and put feeling into it because the crowd could see it if you didn’t.

Whipper had a way of making people gravitate towards him. “He was a gentle giant, both inside and outside the ring,” Persechini says. “He was a warm, gentle man and a special person. He did nothing but help people.”

Had his career not ended prematurely, Persechini thinks Whipper might have stayed in the wrestling world for at least a few more years, in some capacity.

Whipper Billy Watson, a man who provided so much entertainment to wrestling fans in the sport’s golden era, and brought people together in ways no one else could, died on February 4, 1990 of a heart attack at his winter home in Florida. He was 74.

His death made headlines in newspapers across the country as hundreds of friends, family, and fans gathered at his funeral. Persechini was one of the 8 pallbearers – another was Gene Kiniski, one of Whipper’s “arch rivals” from his wrestling days. Kiniski flew from Vancouver to attend the funeral and say goodbye to a man who he had travelled up and down the road with for years. In fact, it was in a tag team match against Whipper that Kiniski made his debut in 1956.

Even decades after Whipper hung up his wrestling tights, Persechini says he never spoke about what went on behind the curtain in wrestling. Long-removed from a business that was engrained in him, Whipper stayed tight-lipped. Professional wrestling historians maintain that wrestling matches have always had pre-determined outcomes. Whipper adamantly disagreed. “We don’t fix that, we never did that,” Persechini remembers him claiming. He wasn’t about to argue with the Whip.

And why would he?

“It looked real to me,” Persechini reasons. “And it was a good entertaining show. It was art.”

Appreciation is expressed to Joe Persechini, who dug into Whipper’s personal archives and provided photos and momentos for this article. Greg Oliver has written six books about professional wrestling. His latest books, though, are all hockey-related: Don’t Call Me Goon, The Goaltenders’ Union, Written in Blue & White, and Duck With The Puck. Visit SLAM! Wrestling at: http://slam.canoe.ca/Slam/Wrestling. For more information about Easter Seals, visit: www.easterseals.org.